Many times, when we view an abandoned space in an otherwise populated area, our automatic reaction is to mourn the loss of its use value—here is a house that’s been allowed to decay instead of provide shelter, here is a piece of land which could be productive, a lawn, a park, a homesite, but is instead overtaken by weeds. “What a waste!” we think. In large cities that have suffered population loss after deindustrialization, places like Baltimore and Philadelphia, entire neighborhoods are mottled with abandoned spaces, lost usefulness. Even the house cats are feral.

One common desire we have is to want to rehab and reclaim—undo the harm nature or other humans have done and bring the space back into perfect human usefulness. This idea has been slickly packaged and sold to us in so many iterations of the home renovation show. As the tide of exodus of the middle class from cities turns and metro populations begin to swell again, land values increase, old homes are renovated and new homes are built in old spaces. In the early stages of redevelopment, as the wealth of neighborhoods increases along with the expectations of the residents, the “eyesore” of the abandoned lot is no longer tolerated. But as changes begin to materialize, before vacant land gives rise to condominiums, businesses, and more cultivated permanent uses, one of our favorite initial practices is to transform it more moderately. Say, into a community garden.

Not surprisingly, Detroit is a hotbed of urban farming and gardening, due to its vast expanses of vacant land within city limits. Which, until a few years ago when an urban agriculture ordinance was passed, were technically illegal. Urban farms and community gardens in general have a spark of anti-establishment sentimentality to them; they serve to both buck the corporatized and, in many ways, broken food system and act as a patch for it. And sometimes this is welcomed by the inhabitants of the neighborhood, and sometimes it’s not.

There are no doubt countless benefits of urban community gardens, both as places for the production of food (and education of growing food as well as nutrition) and the preservation of green space—but all of these benefits certainly reflect on a specific value system (how we should eat, grow and obtain food, utilize land, and so forth) which is by no means universal. However, the idea of growing food in urban spaces certainly is historical. In the US, many community garden projects can trace their history, directly or indirectly, to the victory gardens of the two World Wars. While today’s urban gardens are often praised for their role in such noble tasks as combatting food deserts and improving the aesthetics of derelict neighborhoods, their ancestral garden was seen in a much different light—working for the system itself.

The war efforts of World War I and II had devastating impacts on industrial food production. Farmers were short workers due to the draft, production and transit shifted focus to war needs, and much of the food that was produced was sent overseas to feed soldier and refugee populations. The end result in the US, as well as many other countries affected by the great wars, was the dearth and subsequent rationing of food. In order to alleviate strain on our food system, consumers were asked, en masse, to stop participating in the food economy as much as possible, and return to the practice of self-sufficiency, growing one’s own food. As one publication implores:

. . . it is the only way America can produce the vast shiploads and trainloads of food our own fighters and workers and allies must have in order to win the war ; it is one way in which you can directly contribute to this victory.

The pamphlet, put out by Union Fork and Hoe Company (Columbus, Ohio), goes onto explain the importance of frugality during that time. Much as we are encouraged today to buy locally-grown food both to reduce transit times of produce, thus reducing emissions, and the wastefulness of extraneous packaging, they assert, “Fresh and canned food that is eaten where it is grown saves freight cars and trucks for war transportation as well as thousands of tons of metal ordinarily required for cans.” They further encouraged canning to preserve summer-grown foods for eating during the winter months in temperate climates, as well as the repairing of tools instead of purchasing new ones–meaningful coming from a company that manufactured farming implements! These same practices today are hallmarks of the modern sustainability movement.

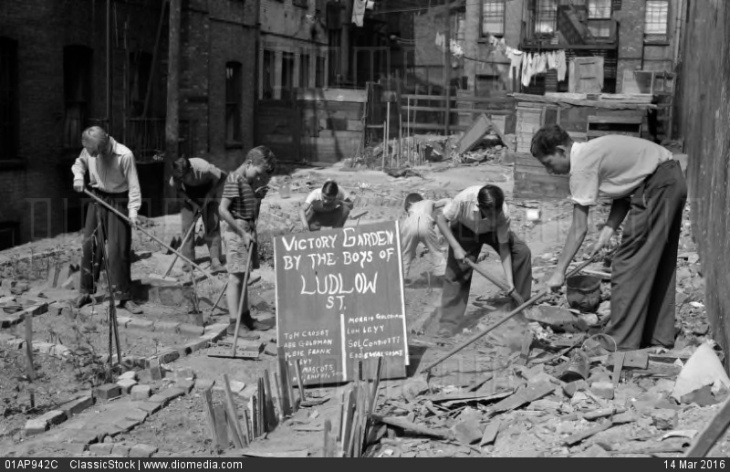

Making use of what you already had, rather than taxing the spread-thin system of production, was the underlying tenet of much of the educational materials surrounding victory gardens. The reuse of old tools was only a start. The repurposing of space was by far the largest example of prudence. In urban locations in the US and England, victory gardens began proliferating in disused spaces–the edges of railways, rooftops, and vacant lots.

Interestingly enough, the USDA and government officially discouraged tearing up one’s lawn, or growing food in urban spaces, concerned with the quality of soil or lighting, and its effect on food production. A brochure put out by the Ontario Department of Agriculture clarifies this stance:

Unless conditions are favourable . . . a vegetable garden should not be undertaken. We cannot afford to waste seed, fertilizer, equipment and energy unless location and soil are suitable and the gardener is determined to follow through to harvest and use.

Despite official discouragement, it still happened, in Canada as well as the US. By 1945, Brooklyn was home to more than 17,000 victory gardens, occupying backyards, empty lots, as well as municipal property, with an estimated 230 acres under production. New York City as a whole had 400,000 plots. Chicago had 172,000. Every major US city was home to a burgeoning of annual gardens in backyards, empty lots, and even parks. You can still visit the 500 Fenway Victory Garden plots in Boston, now a historic landmark.

Gardeners with limited access to land, in urban and suburban areas, would often use whatever space was available to them. Here, a man tends a garden planted in the narrow strip of yard between a street and a sidewalk:

In England, where space was at an even greater premium, agricultural efforts began appearing in the strangest of places. Football fields became grazing pastures for sheep, and there was even a garden cultivated in the crater of a bomb.

While repurposing unused land, especially in urban settings, is again popular today, victory gardens had a different agenda. Instead of defying the (food) system, or addressing problems within it, victory gardens were borne out of a spirit of camaraderie and solidarity in everyday life; they were contributing to the food supply, not creating an alternative one. This sort of gardening was sold as something greater than merely growing vegetables—they were helping the war effort, combatting fascism with their hoes and seeds. But on a more basic level, the gardeners gained satisfaction from knowing that they were a contributing member of their society, and that the work they did directly aided its success. Through the cultivation of life into food for themselves and their communities, they were doing something so purely useful: providing sustenance. And their efforts were huge. These gardens generated an equivalent amount of food at the height of the war as was produced by farms and production plants.

It is stunning to think just how much was produced off of extraneous land resources: 40% of produce came from about 20 million home gardens in 1943, many of which were cultivated on land that had been previously used for other purposes, or not at all. Ultimately, victory gardens had tremendous success taking these “nonproductive” outlier tracts and making them once again “useful” to the human population and our very human efforts at maintaining our fragile civilization.

The statistics that illustrate the success of food production from such motley spaces are impressive, but also lead to a critical consideration of the very human differentiation of the productive versus the nonproductive, and the stakes of production itself. In our contemporary society, we have many extraneous resources that we allow to be fallow or even go to waste. Half of all food in America is thrown away, so much land, water, and fertilizer are used for decorative, underutilized lawns instead of for food production, and, according to a report by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, more than a quarter of the entire earth’s terrestrial surface is used for livestock grazing, which of course is the most inefficient form of agriculture by far (we could feed multiple planets if we simply grew crops on the same land!). In other words, we have an enormous hidden capacity for food production, and are no where near operating at full capacity. With all of the corporate claims that only industrial agriculture can “feed the world,” this fact is reassuring.

While many of the spaces employed for victory gardens were domestic backyards that had simply not been previously used for growing food, some of these spaces were the superfluous tracts of land (no man’s land) that go disused because they are not seen as essential for our human needs. These are the little strips of land along railroad tracks that teem with wildflowers and grasses—quite productive, just not for us. These are the lots, once used or once meant to be used, that dot our urban landscapes and are allowed to slowly transform into botanical chaos—first the grass remains unmown, then the most virile plants, the dandelions and thistles arrive, their seeds blown in on the breeze. Weeds are not just plants that are seen as having little human use—they are also tough, sturdy; they take root in the least hospitable places and flourish. I imagine the great efforts it took for the victory gardeners to reclaim these spaces, once the weeds had set.

In the summer of 2015, Jeremy and I re-cultivated his grandmother’s old garden beds, and made a few new ones of our own beside them, selling our surplus at the local farmers’ market in Clinton County, Ohio, and lugging as much as we could back to Lancaster at the end of the summer. While we had plans to continue to cultivate that space each year, fortune brought us back to Pennsylvania last summer before we were even able to plant the nearly 700 transplants we had started from seed.

Feeling a bit defeated from last year’s lost effort, we jokingly applied the term “Victory Garden,” to our allotment this year, a small plot we are renting at Lancaster County Central Park. It is newly cultivated, our space a 20×55 foot tract of a tilled and divvied up grassland.

We have plans to grow over 100 varieties of fruits and vegetables from our collection of purchased and saved seeds. Included in our plantings are some specific heirloom varieties recommended to victory gardeners of the past: Bronze Arrow and Forellenschuluss lettuce; Red Russian Kale; Detroit Dark Red, Bull’s Blood, and Chioggia beet; Purple Vienna kohlrabi; Yellow Crookneck squash; Yellow Pear, Brandywine, and Cherokee Purple tomatoes; Stowell’s Evergreen and Golden Bantam sweetcorn; Early Russian cucumbers.

Delving into the history of victory gardens has shown us an array of techniques to add to our skillset, and also reminds me that the methods of successful gardening are often age-old, not modern discoveries, despite the recent resurgence of organic and small-scale agriculture. Pamphlets encouraged enhancing production in small spaces and ensuring a constant stream of fresh foods by “companion cropping,” succession planting, and planting cold weather vegetables on the heels of warmer crops for multiple harvests—the same things I learned studying sustainable agriculture.

We recently fenced in our plot with welded wire to keep out the deer and rabbits. The soil is full of grubs, spiders with their egg sacs, and small ants. Tree swallows swoop overhead, ready to eat the seeds we plant. White quartz stones obstruct our spades, and morning glory and grass are already sprouting from the freshly-tilled earth. We have yet to return home without plucking a dog tick from behind someone’s ear. Though these plots are touted as being “organic,” it feels as though we are, in actuality, fighting nature in order to cultivate them. I suppose this is the state of our current existence as a species—entirely reliant on the thwarting or manipulation of the natural world. While I value the opportunity to grow food for our family in this space, I, at the same time, lament the lost meadow.

You must be logged in to post a comment.